Conversation With a Transportation Planner

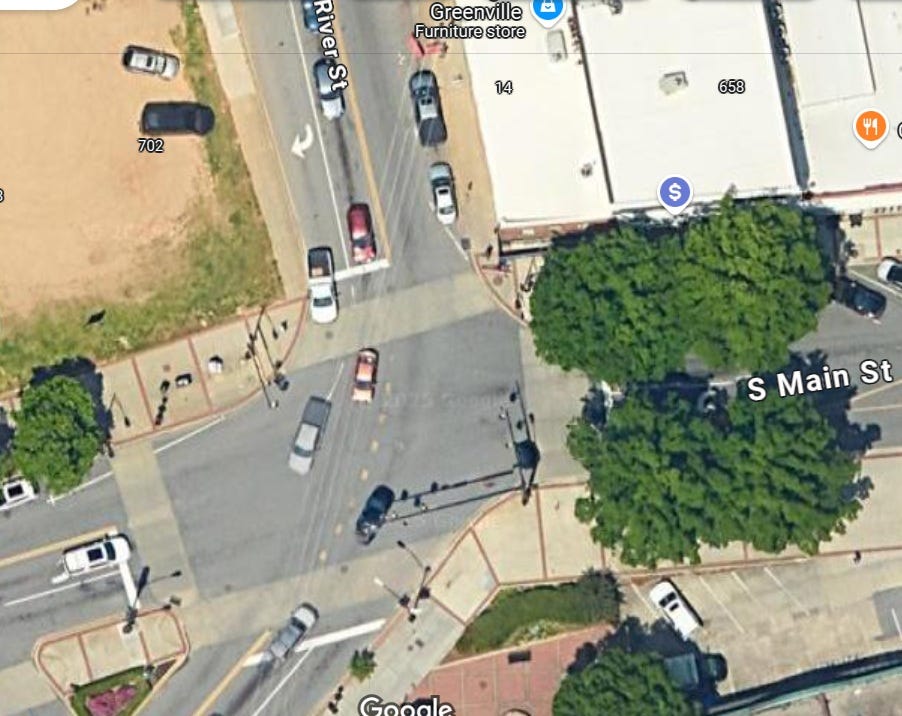

A few weeks ago, while enjoying drinking coffee at a coffee shop here in Greenville that we find pleasurable because it evokes a “European” ambiance (a shop fittingly named “Old Europe”), I noticed something I’ve observed several times in the past. A nearby street intersection occasionally is the source of honking car horns. The problem, I quickly noticed, was the inappropriate, dangerous design of the intersection. See photo.

Because of my nature of not being able to bite my tongue, I wrote and published a blog post about the problem.

I was grateful to see that this blog about the need to improve the street intersection in elicited a detailed, intelligent response from a local transportation planner.

The following is my response to his comments.

Jonathan [not his real name], I'm flattered by your detailed, wise comments in response to my recent blog regarding my design recommendations for the Augusta Street/South Main Street intersection in Greenville.

Like you, I'm battle-worn on each of the political obstacles you cite. I'm happy to hear that you agree it seems doable from both a design and cost perspective. Much of this is having the political leadership — leadership that the City showed with the Main Street Road Diet in the 70s and the Liberty Bridge in the 80s, and the many other projects the City has installed to appropriately slow motor vehicle travel and create more attentive driving. Achieving these sorts of improvements is a reliable test as to whether the City is serious about its goals of improving transportation safety, increasing bike/walk/transit trips, and improving the health of town center retail activity, town center homes, and office establishments.

As you indicate, an enormous obstacle is the state Department of Transportation (DOT) ownership of the streets, as the DOT mission severely undermines each of the goals I mention above — that DOT mission narrowly and blindly seeks ruinous objectives: maximizing motor vehicle speeds and maximizing motor vehicle volumes.

In a town center that must have slower, attentive, human-scaled conditions to thrive, the DOT objectives are a recipe for degrading and hobbling a town center. As I note in my essay, it is far past time that we recognize that while higher speeds and larger dimensions may be appropriate in outlying drivable suburbs, they are deadly for a town center. In a town center, motorist speeds and convenience must be secondary to the need to create a safe, inviting, vibrant town center.

The tradeoff of accepting a few added seconds of travel time and a slightly increased level of inconvenience should be considered a welcome bargain when we realize the payoff is a significantly better town center.

In sum, a much better town center depends on either the City assuming ownership of town center streets, or convincing DOT that their higher speed/higher volume mission in all parts of the community needs to instead be one where DOT partners with cities so that its designs are context-sensitive. One size does not fit all. I am encouraged, by the way, to see that DOT seems to be increasingly supportive of road diets.

I'm grateful for that shift. For DOT to be context-sensitive, they need to calibrate their design manual to adopt an urban-to-rural transect. One of the essential pieces of that transect: In the suburbs, the motor vehicle is the design imperative. In the town center, the pedestrian is the design imperative.

An essential objective for promoting a healthy, safe, enjoyable town center, as I note above, is that modest, human-scaled dimensions be used for streets and intersections (as well as parking lots and building heights) in the town center. This is, again, a context-sensitive issue, as dimensions in drivable suburbs tend to be larger due to the higher speed geometries used. By contrast, dimensions must remain modest for the lower-speed conditions that a town center needs to thrive.

Unfortunately, it is not only the DOT that is to blame for their aggressive, single-minded efforts to oversize geometries in town centers (oversizing which induces excessive, dangerously inattentive motor vehicle travel). Another leading culprit for oversizing streets and intersections is the service agencies for the City and County – particularly the emergency services such as the fire department.

When objections from the fire department or transit service prevent the use of slower-speed (that is, more modest, human-scaled) dimensions for streets and intersections, overall city and neighborhood objectives are harmed because we end up suboptimizing the “needs” of an oversized fire truck or bus.

A well-designed study conducted in Longmont, Colorado, by Peter Swift showed this conclusively.

In that study, Swift showed that when street dimensions were enlarged to produce faster fire truck response times, the injuries and deaths averted by faster fire trucks were far outweighed by the increase in passenger vehicle injuries and deaths caused by the enlarged street dimensions (dimensions that induced dangerously higher speed and inattentive driving by the far more common passenger vehicle trips). Oversized dimensions demanded by the Fire Department – in the name of improved safety -- tragically and ironically resulted in a net increase in community injuries and deaths. This is because fire injuries and deaths are much rarer than passenger vehicle injuries and deaths.

In other words, by suboptimizing on fire safety by speeding up fire trucks, we end up increasing the overall number of community injuries and deaths. Fire safety is a subcategory of the broader life safety. For a safer city and safer neighborhoods, then, the key is to focus on the umbrella of life safety rather than the subcategory of fire safety. That means our primary focus must be to use the smaller dimensions of streets and intersections which reliably deliver slower, safer, more attentive driving.

In sum, by designing our streets for the rare and oversized fire truck rather than the common, smaller-sized passenger vehicle, we end up dangerously oversizing our street dimensions by applying “worst case scenario” geometries for the rare large vehicle. Doing this drastically increases the likelihood of excessive speeds and excessive inattention by motorists due to “risk homeostasis,” whereby humans drive a vehicle at the highest possible speed (and devote the least amount of attentiveness) that allows them to still feel safe. This speed and inattentiveness ratchets up each time we increase the dimensions of intersections and roadways and clear zones. The result is a net increase in serious injuries and deaths in our community due to the increased likelihood of vehicle crashes caused by speeding and inattentiveness.

Designing our streets for the rare, oversized fire truck is therefore backward.

For a safer community, we must instead size our fire trucks (and buses) to fit the design dimensions of a safe street. That has led several communities – particularly in Europe – to include in their fleet of fire trucks and buses a set of smaller vehicles so that they can nimbly navigate smaller, slower, safer neighborhood streets. An example of this is shown in the photo comparison above.

That is, a street using a low design speed.

Which is, by far, the safest way to design a street.

In the rare event that it is not possible for a fire truck or bus to promptly pass through a slower, safer, more human-scaled street or intersection equipped with, say, a traffic circle or bulb-out or raised median, a common solution is to use a “mountable” curb or “apron,” which enables larger service vehicles to mount an apron that is much less mountable by a passenger vehicle.

Or to have a connected street system where the emergency vehicle can use a parallel, less-congested route. Which, by the way, is a common street design in town centers such as what we find in Greenville.

Greenville must therefore adopt a policy of context-sensitive service vehicle sizes. While it is perhaps true that larger fire trucks and buses make sense in suburbs, the fleet of fire trucks and buses used in the town center must be smaller in size. Otherwise, Greenville becomes its own worst enemy by using oversized fire trucks and buses in the town center. Oversized service vehicles tend to obligate cities to dangerously and otherwise counterproductively oversize its streets and intersections to accommodate the oversized service vehicles. A corollary to this oversizing problem is that cities must prohibit the use of oversized commercial delivery trucks entering the town center.

Another essential principle that must be acknowledged: When it comes to motor vehicle travel, there are no win-win tactics. It is a zero-sum game. In other words, invariably, when we make it easier or faster to travel and park by motor vehicle, we always make it more difficult, less safe, less convenient, and less enjoyable to walk or bicycle or use transit. Motorized travel, therefore, is a self-perpetuating downward spiral. The more we convenience motorized travel, the deeper is the hole we dig and the more locked in we are. The more unsafe and unpleasant life becomes for those who walk, bicycle, or use transit in the town center.

A third essential principle: To increase walking and bicycling and transit trips, it is not about providing more or wider sidewalks, more bike lanes or paths, or more frequent and higher quality transit. It is about taking away space, speed, and subsidies from motor vehicles.

Finally, level-of-service standards (LOS) that strive to maintain free-flowing car traffic are a ruinous way to measure community quality.

First, it strives to maintain or increase speed and convenience and inattentiveness for motorized travel, which maintains and increases per capita motorized travel. Increasing per capita motorized travel is a powerful recipe for destroying quality of life, as what I call "happy cars" have objectives that are largely the opposite of happy people. Cars “like” the opposite of community quality of life. The car “wants” high speeds, enormous setbacks, wide dispersal of homes and destinations, bright lights, gigantic road and intersection, and structure size, and isolation from others (especially from other vehicles). People, by striking contrast, tend to want the opposite: slower speeds, low lighting, human-scale sizing of roads/intersections/structures, small setbacks, proximity between home and destinations, and encounters with other humans.

Far better LOS standards — at least for a town center — would be measuring levels of building vacancy on a street, how many people are walking on the sidewalk, how many homes are nearby, how slow the town center speeds tend to be, the amount of active retail and culture vs deadening office buildings, the number of destinations (walkscore.com) a person can walk to, and so on.

It is essential to realize that motorized LOS standards are a powerful sprawl engine. Why? Because in any community, higher levels of speed and space for motorized travel will always be found in sprawling, distant suburbs.

Town centers — where we want to encourage an increase in compact development, infill, and housing (due to the many benefits that increase provides) — tend to have comparatively low LOS for motorized speed and space. Adopting a motorized LOS, therefore, aggressively pushes new development to the sprawling places we don't want it to go (due to all the negatives of sprawl) because sprawl is where the abundant LOS is found for motor vehicles. LOS standards, in other words, make it far more costly (it is already costly) to engage in infill development (think of the astronomical costs of widening roads or adding parking in the town center compared to the suburbs). If you want to find available LOS, it is almost always found in sprawl locations, not the town center.

Indeed, when I worked as a long-range town and transportation planner in Florida, the State of Florida realized its road LOS standards were ruinously promoting sprawl, so they revised the Growth Management Laws so that cities and counties could create "exception areas" in town centers (i.e., not using LOS in the town center).

LOS standards (that is, striving for convenience and free-flowing conditions for motor vehicles) and larger service vehicles may be great in the 'burbs.

They are terrible in a town center.