Is Boulder Colorado Full? Should It Stop Population Growth?

For nearly everyone in Boulder, the answer to the question of whether Boulder is “full” and should stop future population growth has been a big, fat YES!!!!! for decades.

“THE TRAFFIC IS GRIDLOCKED 24/7!”

“THE MOUNTAIN TRAILS ARE FULL OF HIKERS!”

“THERE IS NO PARKING AVAILABLE ANYWHERE!”

“MY VIEWS OF THE MOUNTAINS ARE BEING BLOCKED BY SKYSCRAPERS!”

But I’m firmly convinced the answer to the question depends on the lifestyle you are living.

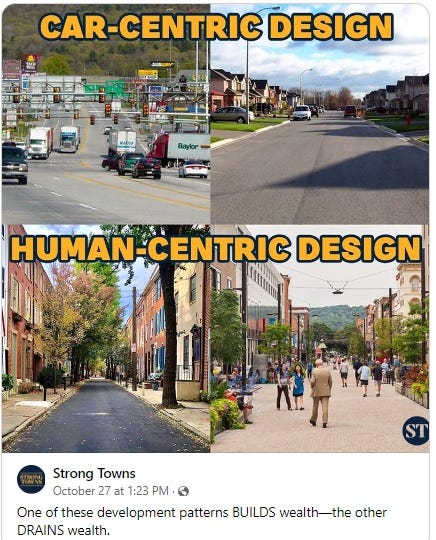

If you live a car-based, driveable lifestyle, where nearly every trip is by car, it is absolutely true that Boulder needs to reduce its population to have five times less people.

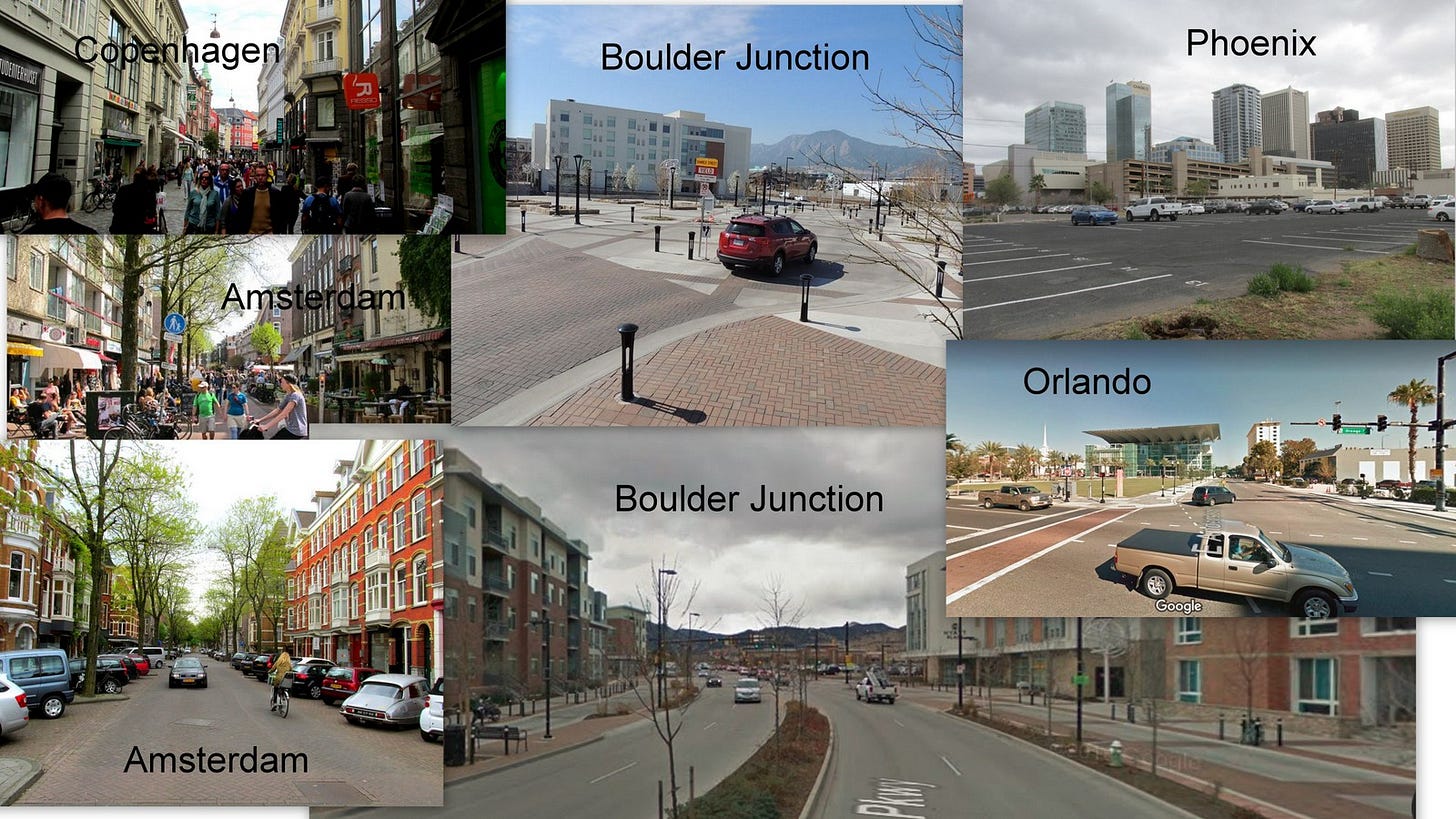

If you live a walkable or bikeable or transit-based lifestyle, on the other hand, it is certain that Boulder needs to have about five times more people. See the images in this blog.

Christopher Leinberger puts it like this:

...walkable urbanity is entirely different than drivable suburbanism. The underlying financial and market principle of drivable development, aka sprawl, is that "more is less"; more development reduces the quality of life and financial returns, leading developers and their customers to perpetually go further and further to the fringe in a fruitless search for very things (open space, drivable convenience, perceived safety, etc.) this development promises. It is a downward spiral. Walkable urbanity works under financial and market principles that "more is better"; as more dense development takes place with mixed-uses within walking distance and multiple transportation options to get there, the place gets better. Hence the environmental, fiscal (government tax base), community building AND project financial elements all become better. It is an upward spiral. - Christopher B. Leinberger, Dec. 20th, 2006. Author of The Option of Urbanism.

I wrote the following after reading Leinberger’s book:

For those living in compact neighborhoods, “more is better,” because more houses, retail, and jobs compactly added to the neighborhood enhance the quality of their walking, bicycling, or transit lifestyle (they can walk, bicycle, or transit to more destinations). By contrast, for those living in more dispersed, drivable suburbs with relatively low densities, “more is less,” because more houses, retail, and jobs added to the neighborhood degrade the quality of their drivable lifestyle (driving and parking is less convenient and more frustrating). “More” for this lifestyle means more difficult and costly to drive a car when new development is added to the neighborhood.

“More is Better”? Or “More is Worse”? The question tends to be answered, therefore, based on where you live in the community.

The above explains why many citizens living in American cities oppose higher density, compact, mixed-use development, as well as taller buildings. Because nearly all residents in American cities live in places where car travel is the only practical way to travel, higher density, compact, mixed-use development, as well as taller buildings, are vigorously opposed as an existential threat to their lifestyle.

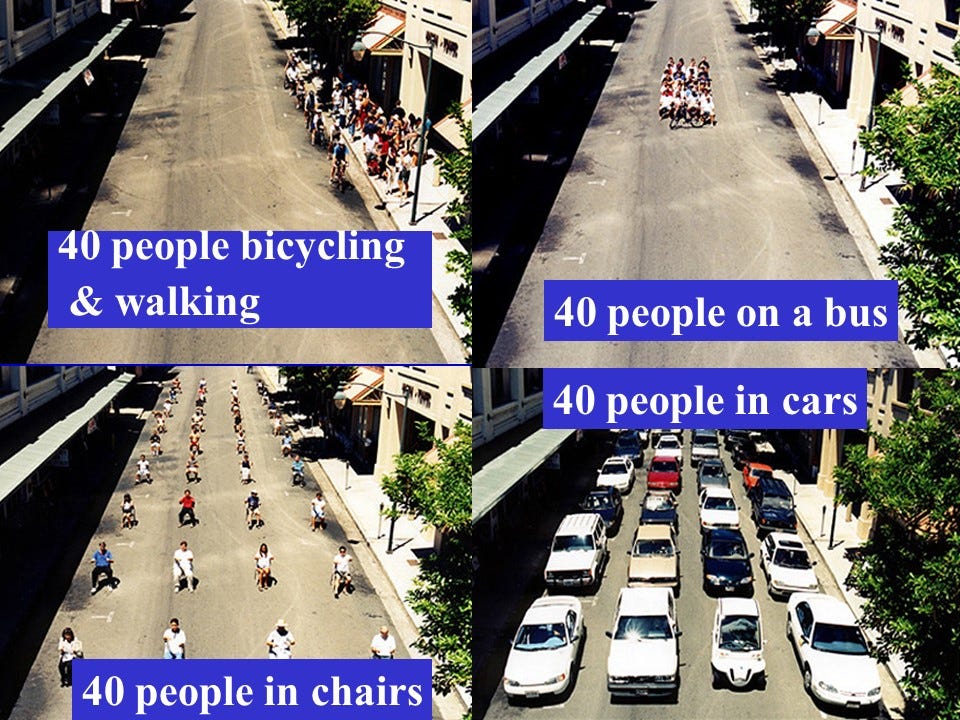

These things, for the motorist, must be prevented to preserve, to the extent possible, a dispersed community layout. A thinly spread-out development pattern is the only possible way for motorists to drive and park their enormous metal boxes (i.e., their cars) in a relatively easy manner. Fewer neighbors (fewer homes, shops, or buildings) means fewer enormous metal boxes for travel. Fewer metal boxes competing for what is now scarce road and parking space.

A big downside to this “more is less” way of thinking and way of designing a community is that a dispersed community ensures that a far higher percentage of people living in the community will be required to travel by car. In other words, in a compact, walkable community of, say, 50,000 people, about 10,000 of them will get around by car. But in a dispersed community of 50,000 people, about 49,000 of them will get around by car.

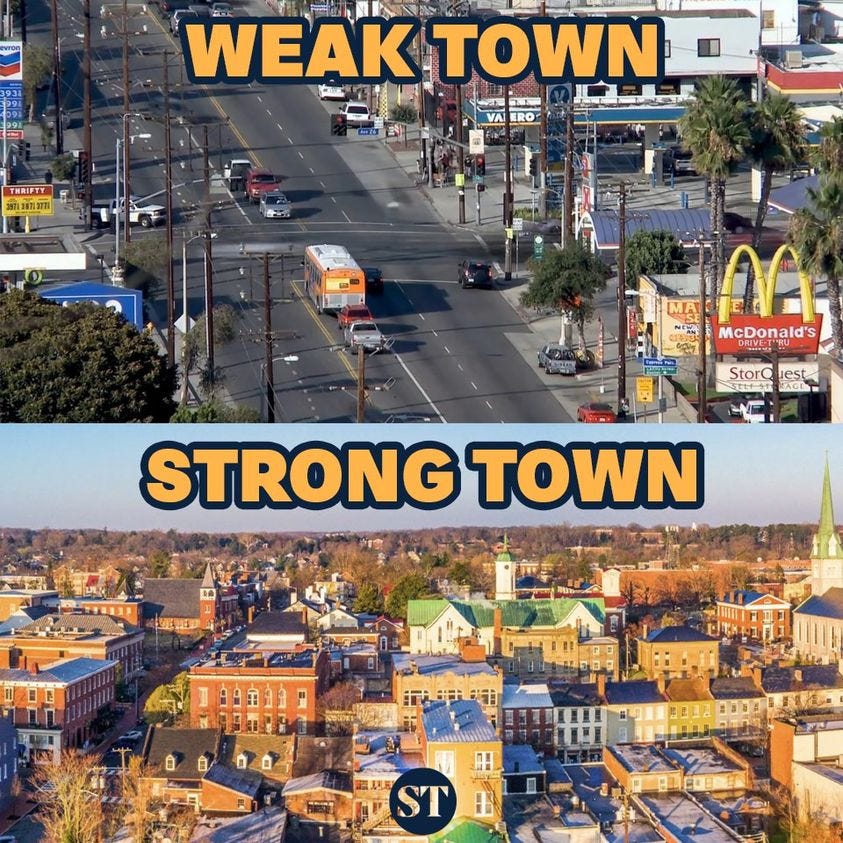

Unfortunately for Boulder, the several decades of fighting to keep densities low (dispersed, that is) in the city have locked the city into an extremely low-density development pattern. That means taxes are far higher and will continue to grow higher and higher into the future.

Why? Because low-density development is a Ponzi Scheme:

Low-density suburbia (80 percent of most cities) comes far short of paying its own way. The meager tax revenues it produces come nowhere near paying for its enormous impacts.

New development in a community offers an initial short-term infusion of additional public tax revenue, which convinces naive city officials that this bump in revenues will persist long-term. Tragically, low-density drivable development patterns quickly demand more services for such things as roads and maintenance and schools and law enforcement and fire services and water and wastewater, and parks than can be funded by the tax revenues their low-density patterns can produce. The result is a rapidly reached financial crisis for local government. A crisis that leads to higher taxes. Or more commonly, lower-quality, insufficient public services.

Suburbia is, therefore, a bankrupting Ponzi Scheme. And a self-perpetuating downward spiral.

It is financially unsustainable because it requires far more in tax revenues than it can deliver in such revenues.

Low-density patterns, tragically, are a trap. Because a drivable lifestyle is highly inconvenient and costly when development patterns are more compact, lower density, dispersed patterns, patterns that don’t come close to paying their own way, have been demanded for over a century, because nearly all of us insist our elected officials only allow that type of car-enabling development pattern.

Because a drivable lifestyle is utterly incompatible with higher-density, compact housing patterns (due to crowding of roads and parking), the drivable lifestyle lived by the large majority of Americans becomes a severe obstacle to providing ample, affordable housing for a workforce needed for a healthy local economy.

When car travel emerged a century ago, we began building our communities to facilitate such travel. We eventually overbuilt for cars and reached a tipping point. A point where driving was the only realistic way for the vast majority of us to travel. That threshold created a world where there is no turning back. We here in America have reached a point of no return. Even Amsterdam is seeing a steady rise in car ownership.