Reforming the Design of American Cities

For the more urban, town center neighborhoods in American cities, the following reforms are essential:

Make it far easier to build accessory dwelling units (ADUs).

Reform motor vehicle parking: Eliminate off-street parking requirements (couple this with adding far more on-street, priced parking). Require that new residential projects unbundle the price of parking from the price of housing. Require relatively large businesses to offer a parking cash-out program for employees. Expand the ease at which developments or businesses can share parking spaces.

Revise regulations to make it far easier to replace off-street surface parking lots with buildings.

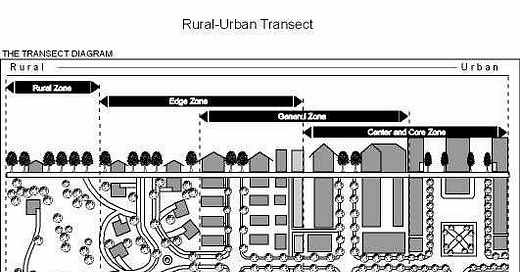

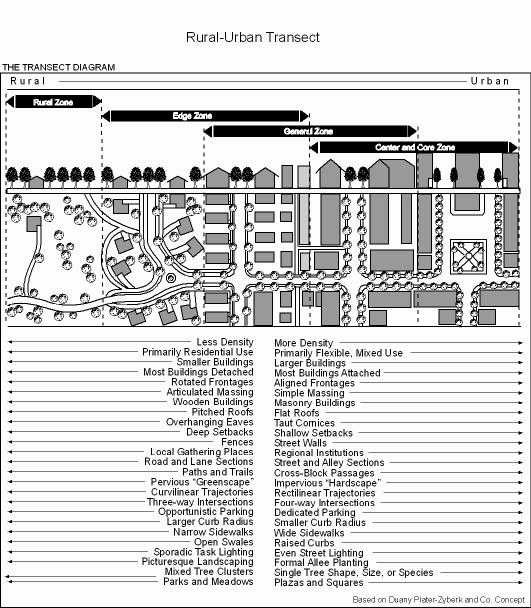

Convert the use-based land development code with a form-based land development code. As a part of that, adopt transect zones that calibrate land development regulations from urban to rural. Neighborhoods in or near the town center should, as part of a form-based code, allow small retail and office development. In neighborhoods built prior to 1940, new development design should be compatible with pre-1940s architecture (incompatible modernist design must be prohibited). Prohibit chain link fence in neighborhoods in or near the town center. Increase allowable residential densities in neighborhoods in or near the town center, and increase the allowable floor area ratio. For neighborhoods in or near the town center, reduce the minimum lot size and minimum lot width, and eliminate landscaping requirements.

Expand the availability or supply of walkable urban housing drastically. For several years, the supply of walkable, compact, urban housing in American cities has been far lower than the demand for such housing. This artificially increases walkable housing costs.

Reduce building setbacks, landscaping requirements, impervious surface requirements, and open space requirements.

Prohibit drive-throughs in the town center.

Essential regulatory and government reforms that are outside of the land development code:

Establish a noise pollution control office that has only two tasks: adopting noise control regulations and enforcing those regulations. Noise regs cannot be adequately enforced by the police dept because such violations will always take a back seat to crimes such as murder or theft or arson. The city is suffering from severe noise pollution. Primarily, this is due to exceptionally excessive and often unwarranted siren use by emergency vehicles. In addition, and particularly in the fall, leaf blowers are creating severe noise pollution for nearly all daylight hours during the week. This is the first time in my life that I have ever lived in a city where it seems as if nearly all property owners on my street use a leaf blower two to three times a week. There are many solid studies showing a link between noise pollution and a decline in property values, not to mention a decline in mental and physical health and a decline in neighborliness.

There are a large number of STROADs in the town center. That is, roads that are oversized and designed to induce excessive motor vehicle speeds. STROADs degrade the value of homes within at least two or three blocks of the STROAD, and bankrupt city, state and federal government (in part due to high crash rates, and the fact that they are a “Ponzi Scheme” in the sense that the low-density strip development that is spawned by STROADs does not pay sufficient tax revenues to pay for the services and infrastructure it requires). STROADs also increase the percentage of residents who make trips by motor vehicle rather than bicycling, walking, or transit (because it is far too dangerous and unpleasant to bicycle, walk, or use transit on a STROAD). STROADS also create high levels of noise pollution, destroy “small town” character and a sense of place, induce high levels of suburban sprawl and strip commercial development, makes the city far more ugly and lacking in civic pride, increases the amount of time devoted to daily travel (largely because they disperse development), promote high levels of water and air pollution, worsen the “heat island” effect, and reduce travel independence (particularly for seniors and children). STROADs must be converted to urban streets via a road diet (i.e., removing excess travel and turn lanes). No street in the town center should be more than three lanes in size. Convert all double-left-turn lanes to single-left-turn lanes. In suburban locations, replace traffic signals with roundabouts.

Convert all one-way streets in the town center back to two-way operation.

New government buildings and renovations must only be able to use classical design.

Revise traffic signal timing to be designed for bicycling and bus speeds rather than private motor vehicle speeds.

Restore former alleys and cross-access in neighborhoods and require alleys and cross-access in new neighborhood construction.

Keep service vehicles in the city relatively small so that large vehicles (buses, fire trucks) don’t obligate engineers to design street dimensions to the point of over-sizing such dimensions. Incrementally replace over-sized service vehicles with smaller vehicles in future years. Designing for the infrequent large fire truck may, on balance, be more harmful than helpful because it may encourage improper travel behavior by the more frequent users of neighborhood streets. For example, larger trucks often result in the construction of larger turning radii, yet the benefits obtained by the rare truck are outweighed by the frequent passenger car, which is encouraged to drive faster due to the larger radii (Motorists tend to travel at speeds they feel safe at, and a street designed for safety at high speeds thereby result in higher average travel speeds.) Faster vehicle travel discourages travel by pedestrians and bicyclists, who feel less safe with the higher speed traffic. In addition, the higher average speeds make the neighborhood less livable because the neighborhood not only sees a restriction in travel choice but also suffers from ambient noise level increases. Designing for “possible” uses such as large trucks, instead of “reasonably expected uses” such as cars, leads to worst-case scenario design -- not a proper way to design a livable or safe neighborhood.

Remove all slip lanes in the town center, and convert continuous left-turn lanes to raised medians and turn pockets.

Adopt an Unbiased and Plain English Stylebook for city staff to use for written and oral communication. This is necessary because the City regularly uses highly biased language, and confusing jargon that is very difficult for citizens to understand. And that is highly detrimental to public engagement in the city.

To more effectively promote needed infill development in the town center, reform taxation by establishing a land-value tax. Land value taxation (LVT) is the policy of raising tax revenues by charging each landholder a portion of the value of a site or parcel of land that would exist even if that site had no improvements. It is different from a property tax, which includes the value of buildings and other improvements on the land. The common use of the property tax therefore discourages building improvements or expansions, and encourages the speculative retention or under-use of downtown property (typically by creating a surface parking lot), because development of the property or building improvement of the property financially penalizes the property owner by increasing taxes. While not a pure LVT system, Harrisburg PA has substantially reduced the vacant land found downtown by taxing land at a rate six times higher than improvements on the land. The development of vacant land in Harrisburg has been far in excess of similar cities using conventional property taxation.

Create highly visible gateways that clearly announce to motorists that they are entering a lower-speed, human-scaled community.

Revise the City Street Design Manual to replace “forgiving street design” with “attentive, low-speed design.” The maximum design speed in the town center must not exceed 20 mph.

To increase transportation funding equity and diversify funding, establish or enhance one or more of the following: (1) a Vehicle Miles Traveled fee; (2) a more comprehensive, dynamic market-based priced parking program; (3) priced roads; (4) pay-at-the-pump car insurance; (5) weight-based vehicle fees; (6) gas taxes; (7) mileage-based registration fee; and (8) a mileage-based emission fee. If possible, make such new taxes/fees revenue neutral by reducing or eliminating other fees/taxes when the new user fee is instituted.

Increase the supply of affordable housing by creating land use patterns that reduce the number of cars a household must own. Ease restrictions on accessory dwelling units, mixed-use, and higher occupancy limits. Require new development to unbundle the price of parking from the price of housing. Unbundling is an important way to make walking and bicycling lifestyle more advantageous than driving.

Effectively Slowing Motor Vehicles Through Horizontal Interventions to Dramatically Improve Transportation Safety

Slowing down motor vehicle speeds through effective traffic calming measures is crucial. The best way, by far, to slow motor vehicles is not to use “vertical” interventions such as speed humps, but to use “horizontal” interventions. Examples of horizontal interventions include: (1) Road diets (where excessive street lanes are removed). The most common diet is going from 4 lanes to 3; (2) Landscaped or hard-surface bulb-outs (usually used to frame on-street parking or create a mid-block pedestrian crossing). Bulb-outs are admirably used on some streets in American cities. This “pinching down” the width of the street creates a one-lane-wide pinch point that obligates motorists to “give-way” when a motor vehicle approaches in the opposing direction; (3) Chicanes, which are a form of bulb-out that obligates motorists to move in a slower, weaving, more attentive pattern; (4) Traffic circles and roundabouts; (5) Installing on-street parking on streets without such parking. Again, this narrowing of street width works best when a “give-way” street is created; (6) Reduce the width of travel and turn lanes; (7) Establish several give-way streets and woonerfs within the city; and (8) Installing formally-aligned street trees abutting the street to create a sense of enclosure and human scale.

Install protected bike lanes in the city, and adopt the “Idaho law” in the city (a law that allows cyclists to treat stop signs like yield signs, and red-lights at intersections like stop signs).

Plant large canopy street trees on as many street blocks as possible (using the same tree species on a particular block – species diversity is created between blocks, not within blocks), retrofit intersections to drastically reduce turning radii, and reduce the height of traffic signals and street signs and street lights.

Each of the horizontal interventions described above is much more conducive to bicycling and emergency response vehicles than vertical interventions such as humps. They are also much better at creating a safe environment for walking. As well as creating the much-needed human scale and sense of place that is lost when we oversize streets and intersections.

Nearly all American cities which adopt this important goal of slowing vehicles and increasing traffic safety engage in the same old ineffective song and dance. They repeatedly use the Five Warnings: Warning signs, Warning lights, Warning education (traffic safety education is a form of victim-blaming), Warning paint, and Warning enforcement to promote safety. Such campaigns border are patronizing and profoundly ineffective in improving safety. They are used repeatedly by elected officials, however, because they are a low-cost, politically easy way to reduce complaints from citizens.

Note that the Five Warnings were, initially, meaningfully improving safety when first used several decades ago. But they have been so over-used over the past century that they now suffer from severe diminishing returns. In part because they contribute to information overload by being overused, which makes them extremely likely to be disregarded.

After a century of using these ineffective “warning” tools for safety, roadways in cities are – for pedestrians and cyclists -- more dangerous than ever. We must be serious about achieving “Vision Zero,” rather than simply being politically expedient. The City can show it is serious about transportation safety by designing our streets and intersections to obligate motorists to drive more slowly and more attentively. It is long past time to deemphasize The Five Warnings in favor of physically redesigning our streets to obligate safe, attentive speeds. Only then will we make meaningful progress in improving safety for walking, bicycling, transit, and driving.

On my list of top priorities for American cities to become better cities, traffic calming is at or near the top of the list. But calming needs, again, to be achieved with horizontal rather than vertical interventions. Primarily, this is done with road diets, but also includes adding bulb-outs, on-street parking, traffic circles, raised medians, and roundabouts.